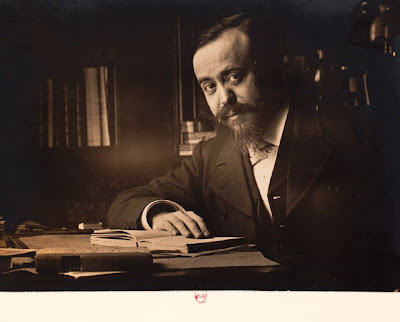

Paul Dukas (1865-1935)

Paul Dukas’s writings are principally tied to his activity as a music critic, which led him to publish over 350 journalistic articles. Dukas turned to music criticism at the age of 26 for a source of income. He began at the Revue hebdomadaire, a recently established cultural weekly which aimed to “give the most complete representation of the contemporary intellectual movement” (as stated in its first issue, May 1892). From 1892 to 1901, Dukas wrote over 150 articles for the Revue hebdomadaire. He also contributed to the Gazette des beaux-arts (eight articles from November 1894 through June 1902), and to its supplement, La Chronique des arts et de la curiosité (193 articles, from 1 December 1894 through 18 November 1905). Dukas ceased activity as a critic in 1905, at which time he was finishing up sketches for Ariane et Barbe-Bleue. Between 1904 and 1930, he participated in several surveys for artistic, literary, and musical journals. In 1919, despite having stepped back from criticism, Dukas was offered a position by Georges-Jean Aubry, director of the Chesterian – a proposition he seriously considered, although ultimately declined. A few years later, at the invitation of Henry Prunières, Dukas did contribute occasionally to La Revue Musicale (five articles from 1923 through 1932). At the same time, he began working for the newspaper Le Quotidien, likely for financial reasons. Dukas, by nature reserved, never published a book or any autobiographical output; the entirety of his published writings are thus concentrated in his critical corpus, partially collected by Gustave Samazeuilh in 1948 in an anthology titled, Les Ecrits de Paul Dukas sur la musique. A number of interesting theoretical writings and analyses of works, probably intended for his composition class at the Conservatoire (1928–35), remain unpublished and preserved in manuscript notebooks at the BnF (French National Library). His correspondence, edited by Simon-Pierre Perret and published by Actes Sud, gives a clearer idea of his personality.

The excitement of musical life in Dukas’s day comes to life through his pen. Through a variety of types of articles (reviews of concerts and operas, articles, obituaries, bibliographies), he described Parisian cultural life in all its diversity, and confided his preferences of composers. He testified to successions and conflicts between schools, trends, and influences – Wagnerism, verismo, naturalism, Debussysme – and participated, as a critic, in the rediscovery of early music, plainchant, Palestrina, and Monteverdi. He advocated for the work of Rameau, Gluck, Monsigny, and Méhul. He supported the early music initiatives of Charles Bordes and his choirs (the Chanteurs de Saint-Gervais and later the Schola Cantorum). A perceptive observer and participant in the creativity of his era, he drew the attention of Albert Carré, director of the Opéra-Comique, to Pelléas et Mélisande in 1898. Four years later, his review of the work opened magisterially: “Something truly special has happened to Albert Carré, director of the Opéra-Comique: he has produced a masterpiece.” Constantly questioning the place and role of art in society, he devoted numerous articles to the significance of music as a universal philosophical force. He was also conscious of the circumstances and social life of artists, and sought to decipher and depict institutions like the Conservatoire and the Académie Nationale de musique (the Opéra). He observed, and sometimes challenged, competitions—most notably the Prix de Rome—and lamented the lack of concert halls in Paris, as well as the absence of bold initiative. Dukas was also attentive to circumstances of production, acoustics, mise-en-scène, décor, and interpretation.

Close friends, such as Magnard, praised Dukas’s integrity. Magnard wrote to Dukas in November 1904, when the latter had just devoted an article to his third symphony: “Thank you. I am all the more touched by your accolades, knowing your impartiality when it comes to your friends, which is admirable.” (Correspondance, edited by C. Vlach, Paris: Klincksieck, 1997, p. 225.) Dukas made a point of his integrity in response to Saint-Saëns, following the publication of his glowing review of Les Barbares in 1901: “Trust that I have never belonged to any clique, that I am entirely independent and that, if I am persuaded of the weakness of theories of art, then at least those which I believe to be correct are solely the result of personal reflection [...].” (Lettres de compositeurs à Camille Saint-Saëns, edited by E. Jousse and Y. Gérard, Lyon: Symétrie: 2009, p. 159).

When reviewing individual works, Dukas always seized the occasion to broach a broader topic. He would place each work in its musical, social, and historical context, seeking, with diligent erudition, to guide the listener toward understanding. In this way, he tried to develop the public by sharing and clarifying musical ideas, and by helping young artists he found gifted receive recognition. In 1936, Robert Brussel reflected kindly upon his friend’s writings: “He had no time whatsoever for narrow dogmas. [Dukas] judges the man himself, the artist themselves, the work itself; independently from any predefined value system, from any preconceived position concerning trends, genres, techniques or means.” (La Revue musicale, May/June 1936, p. 357.) According to Maurice Emmanuel, these articles reflect a wise and measured judgement: “[Dukas] would not tear down, with a few lines, the fruit of an effort, even when he would let it be understood that such effort was unsuccessful.” Dukas’s criticism was recognised as enlightened, constructive, and intelligent—possessing “the highest and rarest virtues[...]”. (Le Monde musical, 31 July 1935, p. 224).

Pauline RITAINE

Transl. : Peter Asimov

| firstname | Paul |

|---|---|

| lastname | Dukas |

| birth year | 1865 |

| death year | 1935 |

| same as | http://data.bnf.fr/13893486/paul_dukas/ |