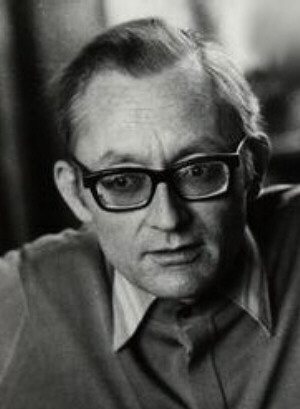

Jean Barraqué (1928-1973)

Between 1951 and 1972, Jean Barraqué wrote much in the same way as he composed: his texts reflect his theoretical engagement, his technical and analytical needs (for his general musical understanding as well as for pedagogical and public dissemination), his sense for (sometimes fierce) polemic, and his general asceticism—or rather, an ethics valorising romantic categories of the sublime and the tragic, of night and of death. These texts, enriched by his study of the classical, romantic, and modern masters, exist in an eminently dialectical relation to his compositional practice. Setting aside short articles (including occasional concert reviews and analytical notes for dictionaries), verses for his compositions or planned compositions (...au-delà du hasard, Chant après chant, Lysanias and Portiques du feu), and programme notes for two works (Chant après chant and Concerto), his writings include a book on Debussy (Paris, Seuil, 1962); a guide to musical analysis (Guide de l’analyse musicale) and over sixty short analyses (in Le Guide du Concert); plus some forty articles and interviews, most of which are collected in a volume (Écrits; Paris, Publications de la Sorbonne, 2001). This corpus may be grouped into five phases, which will be surveyed chronologically.

After having condemned the expressionism of Berg and Schoenberg (their assimilation of the tone-row to a theme and their recourse, in their final works, to tonality) and having enthused over the contributions of Webern (his preoccupations with rhythmic-melodic schemata and his organisation of sounds autonomously and within space-time), Barraqué’s first burst of writing came in the context of the newly formed Domaine musical. In 1954—at a time when Barraqué’s thinking was strongly informed by that of Michel Foucault, whom he was seeing—Barraqué contributed to the Domaine musical’s journal (“Des goûts et des couleurs… et où l’on en discute”) and to the Cahiers Renaud-Barrault (“Résonances privilégiées. Leur justification”), and also published “Rythme et développement” in Polyphonie. The first of these articles reconsiders tradition as an unstable network of entangled filiations, which form bridges that are “often as unequal in their breadth as in the substance of their object” (Écrits, p. 69). The second article performs what Foucault would have called an “archaeology” of musical dialectic, and concludes that any authentic creative experience generates its own technique, which brings the artistic experience into being and expresses it in its totality. The third article restricts this archaeology to the realm of rhythm, through analyses of Machaut’s Mass, Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring, and works by Messiaen and Boulez.

This technical dimension remains on display between 1952 and 1957, in a series of contributions to the journal Musica(1954), in analytical notes for the Larousse de la musique (1957 edition), and above all in Le Guide du concert (later, Le Guide du concert et du disque). For the latter publication, his contributions fall into two camps: first, a Guide to Musical Analysis, a regular fixture which ran from 1952 until 1956 in which Barraqué paraphrases (sometimes to the point of copying) the treatises and textbooks which he encountered through the tutelage of Jean Langlais and Olivier Messiaen (Jules Combarieu’s Histoire de la musique, Vincent d’Indy’s Cours de composition musicale, Théodore Dubois’s Traité d’harmonie théorique et pratique, Marcel Dupré’s Cours de contrepoint, and André-François Marescotti’s Les Instruments d’orchestre). The second type of contribution is a series of short analyses of works ranging from Mozart to musique concrète, with a particular emphasis on nineteenth-century repertoire.

The monograph Debussy, published in 1962 in the “Solfèges” series (Paris, Seuil), spawned several additional studies including “Debussy ou l’approche d’une organisation autogène de la composition” [Debussy, or an approach to autogenous organisation in composition] (1965, but derived from a 1962 conference). In Debussy, Barraqué takes on impressionism, Debussysme, and the French interwar school, each of which he deems technically and aesthetically superficial. In contrast, he proposes a reading of the French master in light of 1950s structuralism, viewing in him a precursor: “A creative giant may always be situated in relation to current concerns. In our constantly renewing present [...], a musical work shines in multifarious glimmers; in different eras, new meanings reveal themselves; understandings of a work are thus destined to vary according to the viewpoint imposed by a given moment in History” (p. 6-7). Beyond an annotated biography—offering a rather full portrait of Debussy without leaving aside his “errors”—what matters most in this interweaving of past and present are the sections of analysis given over to Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune, La Mer, and Jeux. According to Barraqué, the eschewal of received forms in Prélude led to an improvisation, combining the inheritances of sonata form, with exposition and development (setting aside its bi-thematic aspect); the sectional construction of lied (ABA) given the “middle section”; and the rules of variation form, given the incessant harmonic transformation of the celebrated flute theme. But Barraqué’s major argument, which aligns Debussy with Webern (as Boulez had also done), is that La Mer introduced “a method of development in which notions of exposition and development coexist in an unceasing flow, such that the work propels itself, as it were, without relying on a predetermined formal model” (Écrits, p. 268). The theory is taken further with respect to Jeux, through the addition of “absent developments”, which activate the listener’s memory and undermine the continuity of the narrative—or rather, which generate an “alternative continuity”, as though the music were unfolding elsewhere in the meantime.

Following those years, Barraqué’s mental fragility placed a serious limit on his publications. Numerous texts and scores remained incomplete—an incompleteness which, for that matter, was elevated to an aesthetic principle—work eroded, menaced by death. Among the few texts that got published were an article on Mozart (“Sa carrière posthume” [“His Posthumous Career”], 1964, in an edited volume)—that “hiatus” (Écrits, p. 133) between Bach and Beethoven, whose incandescent beauty, Barraqué demonstrated, was so unmodern—as well as various autobiographical pieces, characterized by the self-conscious immodesty of a creator who felt himself “obliged to be the greatest” (collected by Raymond Lyon, “Propos impromptus”, 1969). Two further articles from 1968, with self-evident titles (“Messiaen the pedagogue: musical analysis considered as education; or, learning a trade” and “Study of Musical Romanticism, of Beethovenian Trauma”), would remain unpublished at his death.

Also left incomplete were three further analyses which would be published only posthumously: that of the Variations pour piano, op. 27, published by André Riotte in 1982; that of La Mer, edited by Alain Poirier in 1988; and that of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, edited by Laurent Feneyrou in 2001. These are the only traces of the project that Barraqué submitted to the CNRS (National Institute of Scientific Research, France), where he worked from 1961 until 1970, and for which he had envisaged tracing the origin of the “open work”—not in the sense evoked by Boulez or Stockhausen, nor in the sense evoked of Umberto Eco and taken up by Berio and Boucourechliev, but rather in the sense of a contestation of formal archetypes, an absolute manifestation of becoming, as exemplified by several works by Beethoven (String Quartets Nos. 6 and 14, Symphonies Nos. 3, 5, and 9) and Debussy (Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune, La Mer, Jeux, Nocturnes, Études for piano). At the moment when analysis finds itself up against an aporia, achieving exactly what it set out to demonstrate, it resorts to polymorphism: “I believe to be on the path to, if not rigorously defining, then at least truly approaching, through the method adopted, a means of aesthetic and technical analysis which could be at once sufficiently versatile and sufficiently rigorous so that the work, considered from all points of view—melodic, harmonic, rhythmic, orchestral, formal, etc.—reveals the greatest part of its secrets” (Écrits, p. 402). If a d’Indyist vocabulary abounds in his analyses of Beethoven and of Debussy, Barraqué also devises his own analytical concepts, some of which derived from Messiaen’s teaching—note-ton, note-son, correlative-development, poetic mutation, development by elimination—concepts which proved fecund, analytically as well as compositionally.

Laurent FENEYROU

Transl. Peter Asimov

| firstname | Jean |

|---|---|

| lastname | Barraqué |

| birth year | 1928 |

| death year | 1973 |

| same as | https://data.bnf.fr/12394700/jean_barraque/ |

Publications (4)

Translations (3)

3 results

-

Book translation Allemand : Claude Debussy in Selbstzeugnissen und Bilddokumenten

-

Book translation Espagnol; castillan : Debussy

-

Book translation Japonais : ドビュッシー [Debussy]