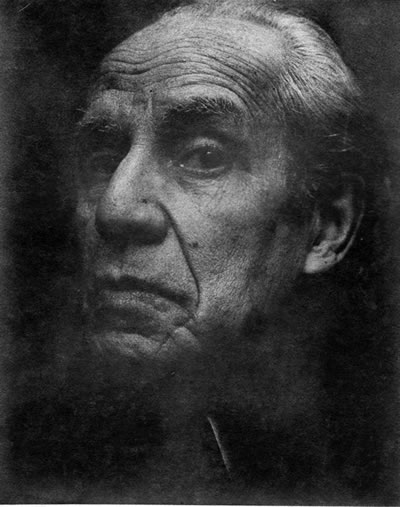

Juan Carlos Paz (1897-1972)

Juan Carlos Paz was a composer, pianist, professor, music critic, lecturer, concert organizer and a figure of Argentina’s musical avant-garde for more than forty years. Born and died in Buenos Aires, he was also a prolific writer. His main literary work remains the vast undertaking of his Memorias, over a thousand pages on “everything I have every thought about” (Memorias I, p. 5), the writing of which occupied the last ten years of his life, a period when he had practically stopped composing. But this interminable series of short essays was merely a prolongation of the three books on music history he published in the 1950s. Above all, they return to the iconoclastic tone of his very first texts, published in anarchist reviews of the 1920s such as La Protesta and La Campana de palo.

In these early texts, Paz undertakes a radical questioning of the institutions and figures of Buenos Aire’s musical life, as in “Reportaje grotesco en el palacio de nuestra crítica musical” [“Grotesque report in the palace of our music criticism”], published in 1922. He also sought to create an international genealogy for himself in music history. Claiming César Franck as an ancestor, the Francophile Paz, took classes at the Schola Cantorum in 1924, and opposed himself with Richard Strauss. At the same time, he became a fierce enemy of Argentine musical nationalism, which then threatened to become hegemonic, instead supporting the universalism he identified first in the modernism of Stravinsky and the Groupe des Six, and later in the Second Viennese School.

Throughout his career, Paz cast himself in writing as an avant-gardist figure in the Buenos Aires musical scene. At times, music criticism, which he wrote with a style as lively as it was implacable, even excessive—so severe were his judgments—, assured him much-needed income (Paz never had a stable job). Still, he was never able to adjust to the routines of job, nor to what he considered its compromises. The professional critic that he could have become can be illustrated by in the regular column he wrote for the prestigious journal Crítica for eight months in 1933. In the early 1940s he became a somewhat regular contributor to the anti-fascist newspaper Argentina libre. In 1942, he engaged in a violent polemic exchange with Alberto Ginastera, a composer some twenty years his junior who, faithful to the nationalist aesthetic and an adept of Béla Bartók, had just referenced tango in a symphonic work. These were two different visions of music, both typical of the twentieth century, confronting one-another in the local arena of the Buenos Aires press.

Thereafter, Paz’s writings became a means to defending his aesthetic and that of his followers and friends in the Agrupación Nueva Música, a group he founded in 1950. Since his Primera composición dodecafónica of 1934—Paz had long practiced and the promoted twelve-tone technique he had taught himself. He even wrote two letters to Arnold Schoenberg in 1938; translated to German by the exiled pianist Sofía Knoll, they remained unanswered. Nevertheless, his correspondence with avant-garde musical figures like René Leibowitz, Ernst Krenek, Henry Cowell, Aaron Copland, Luigi Dallapiccola, and Pierre Boulez, among others, are an integral facet of his writings, one that helped him become part of an international networks of contemporary music, as is testified by the Domaine Musical programming his Transformaciones canónicas in 1958.

Still, it was Paz’s books that made writing an essential part of his work. His first attempt was logically devoted to the inventor of dodecaphonic music and was entitled Arnold Schönberg o el fin de la era tonal [Arnold Schoenberg or the end of the tonal era]. The manuscript was ready for German translation in 1949, as Hermann Scherchen had promised the publication during a visit to Buenos Aires, but this never came to fruition. The book would only appear in Spanish in 1958, but it came to play an important role in the diffusion of atonal and dodecaphonic music in Argentina and in other Spanish-speaking countries, much like René Leibowitz’s works had done for French-speakers. Paz venerated Leibowitz without ever having met him and would later help to translate his work in Buenos Aires.

In 1952 Paz published a modest volume called La música en los Estados Unidos [Music in the United States] that had been commissioned by the Fondo de Cultura Económica. It is a panorama of US-American art music built around the figures of Charles Ives—a new world “maverick” with whom Paz identified—, Henry Cowell, and to a lesser degree, John Cage. In it, Paz violently attacked George Gershwin and “folklorizing” music, as well as “popular music” in general, denouncing without pity the “concessions” of Aaron Copland, who he had met in Buenos Aires in 1941 and who had disappointed him for siding with his rival Ginastera.

These early experiences led Paz to write his Introducción a la música de nuestro tiempo [Introduction to the music of our time], first published in 1955, but best known in the revised and expanded edition of 1971 which remains a reference in Spanish. In this definitive form it became a massive book on twentieth-century music that is most striking for the sheer amount of information it compiles—a feat that is anything but banal when one is writing from a “peripheral” city like Buenos Aires. Paz weaves an epic tale about the “emancipation of dissonance”, beginning with Debussy, Stravinsky, and Schoenberg, and ending in suspense with praise for “open music” and other experimental or “irrational” musics. His international and totalizing ambition is of course limited—only composers from Europe and the Americas are mentioned, plus three pages on Japan—and his disdain for “non-art music” is as radical as it is implied. Nevertheless, the book remains an original extension of the canonic map of musical avant-gardes that offered Paz the occasion to settle scores with nationalist and “conservative” colleagues from all continents and establish himself as an alert and intelligent critic of the most diverse forms of musical experimentation.

Esteban BUCH

07/10/2018

Trans. Chris Murray

Further reading

Jacobo Romano, Vidas de Paz, Buenos Aires, GAI, 1976.

Michelle Tabor, « Juan Carlos Paz: A Latin American Supporter of the International Avant-Garde », Latin American Music Review / Revista de Música Latinoamericana, vol. 9, no2, automne-hiver 1988, p. 207-232.

Esteban Buch, « L’avant-garde musicale à Buenos Aires : Paz contra Ginastera », Circuit : Musiques contemporaines, vol. 17, no 2, 2007, p. 11-32.

Omar Corrado, Vanguardias al Sur : La música de Juan Carlos Paz : Buenos Aires, 1897-1972. La Havane, Fondo Editorial Casa de las Américas, 2010. [L'ouvrage contient une bibliographie détaillée des écrits de Paz]

Camila Juárez, « Juan Carlos Paz: Anarquismo y vanguardia musical en los años veinte », Instantes y azares – Escrituras Nietzscheanas, vol. 10, no8, printemps 2010, http://www.instantesyazares.blogspot.com.

| firstname | Juan Carlos |

|---|---|

| lastname | Paz |

| birth year | 1897 |

| death year | 1972 |

| same as | http://data.bnf.fr/13749805/juan_carlos_paz/ |